History often resembles myth, because they are both ultimately of the same stuff. – J R R Tolkien

In their accounts of what occurred in the past, historians are meticulous while local lore tends toward the mythical. Dutt binds meticulous historical research with local lore and his own stories in his work. Layers of fact and fiction are woven together in each work, looking between the lines of text, lore, built, unbuilt and artefacts.

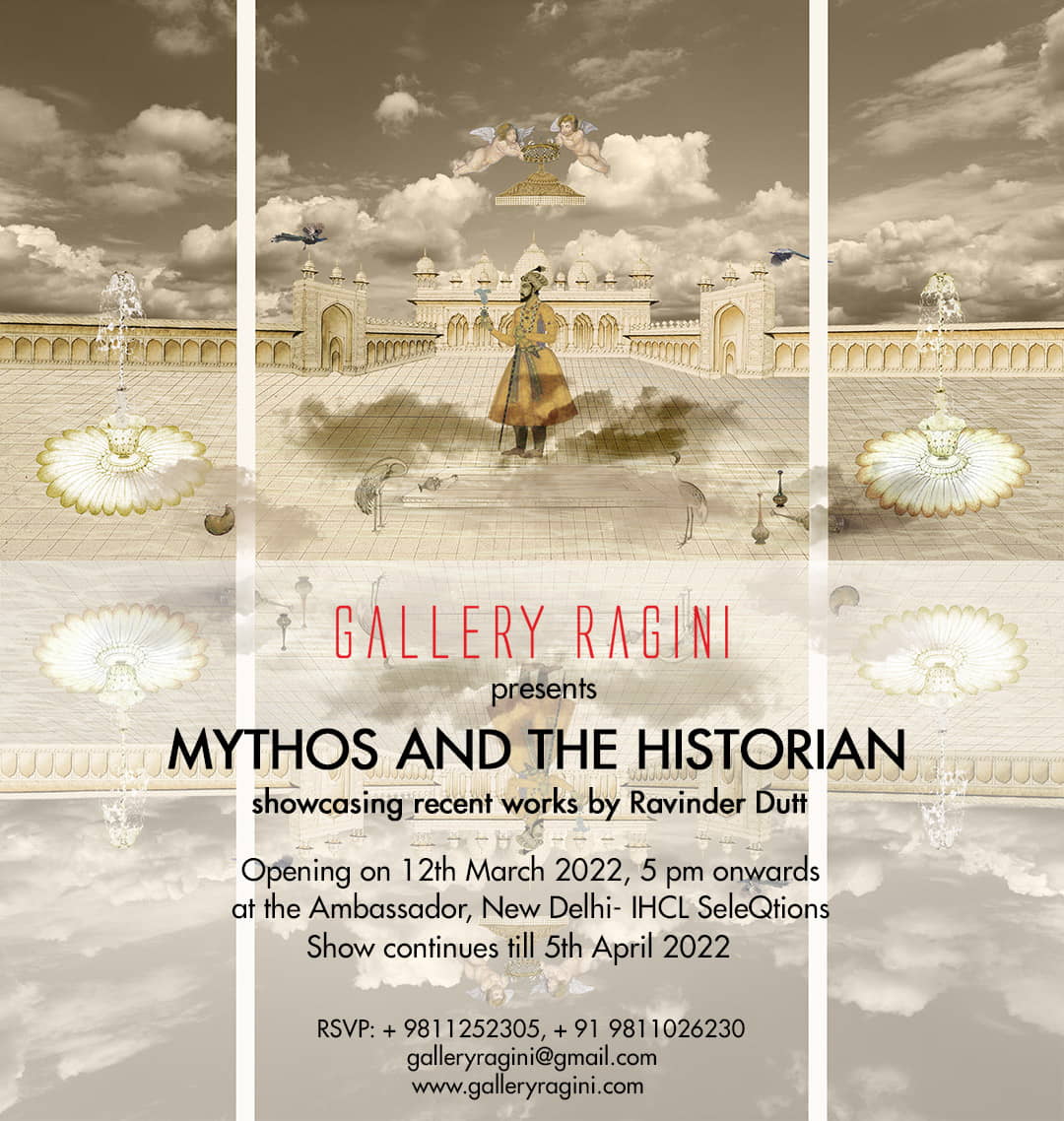

The Mughal Period has a large influence on his creations. The power held by the emperors and the opulence in which they lived are discernable in his work, but as vehicles for the mystical sources of their power and wealth he presents the viewer with. He seamlessly blends the infamous empire and its rulers with mythical creatures, extraterrestrials and even the other world of Agartha; using the supernatural to truly realize the expanse of the Mughal stronghold.

The art, objects and architecture of the Mughal era is the manifestation of great knowledge and technology. In the Mughal Fables, the artist reimagines their rule as one supported by the supernatural that exists on the planet. Ancient pathways led the emperor to the depths of the earth, Agartha, where he gained knowledge and brought it back to his lands.

Sang-e-Badal is set in the Lahore Fort, where the artist conjures an image of a walk in the clouds. Water and itr sprinkled onto marble floors to create a fog – a cloud-like experience for the emperor to fulfill his desires to walk on the clouds. The effect invites birds, creating a sense of levitation for the emperor, and the viewer.

The age-old game of strategy takes a surreal turn in ‘The Game of Chess’. The methods employed by different members of the ruling dynasty in the Mughal era to gain control over the empire become the pieces of this chessboard. The emperor’s supporters in the political arena become medallions on the board, taken from the artists’ private collection.

Other influences come from lost objects in history and the built monuments left behind by different dynasties. Dutt reimagines the fate of the objects, exploring alternate avenues in which they still exist as hidden treasures or for studying by the invader. Thrones have acted like a symbol of wealth and power – the most coveted seat to exist in any kingdom through time. Many of them, however, exist only in history and folklore – lost to wars or trade. In ‘The Lost Throne’, the artist invites us to look at a parchment depicting the fate of the Throne of Tipu Sultan after the fall of Srirangapatna. Many say it was the first object captured by the British, given its fame, and the artist dwells on its fate.

More often than not, the recounting of history chooses sides – right and wrong. Dutt, however, refuses to do so in his work. Rather, he looks back at history with no bias and just to find simple pleasures in fables enmeshed within facts; “Mythos and The Historian” overviews heritage, local legends and stories fictionalized by the artist. He creates each work with layers of all three, bringing them together seamlessly and in his distinct style.

-Ragini J Jain