Stories have always been an integral part of our existence. They seamlessly form part of all aspects of our life, starting from bedtime stories to our records of history to reliving memories of our own personal history. Our first introduction to the outside world is given to us by our parents as they spin stories of fiction and their memories. These spoken words shape our thoughts and experience throughout life.

In any part of the world, the literature that exists can always be traced back to the oral traditions that form part of its cultural history. Even Homer’s Greek classics, which act as the foundation of European literature, stem from spoken poems and epics which slowly faded away with the rise of other forms of media.

India has had a long-standing tradition of oral epics. What separates the Indian traditions from others in the world is the sheer number and variations that exist, passed through generations and some even being recited today. Long epics like the Mahabharata and Ramayana are accompanied by small stories, poems and myths which are part of the myriad diverse cultures that can be found in the country. Vernacular traditions tend to praise kings and local deities or just small stories about people, birds, animals and nature which teach valuable lessons of life.

A flight from Delhi to Raipur followed by a six-hour journey on road leads to Amarkantak, the origin of the Narmada. Patangarh is a further 20km away. There is little to no phone connectivity in the area with a noticeable lack of network towers in parts of the journey. Forced to truly take in the surrounding, you start to notice the small houses, many with intricate paintings and patterns on the wall. Every one of them has a story to tell.

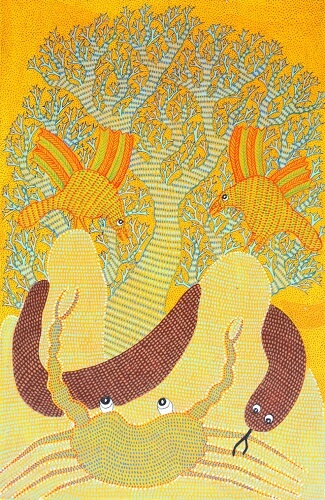

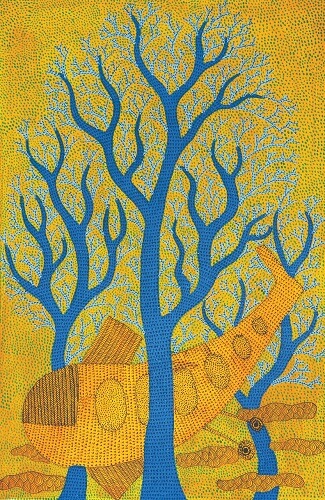

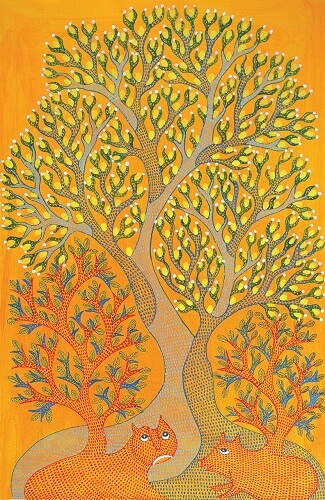

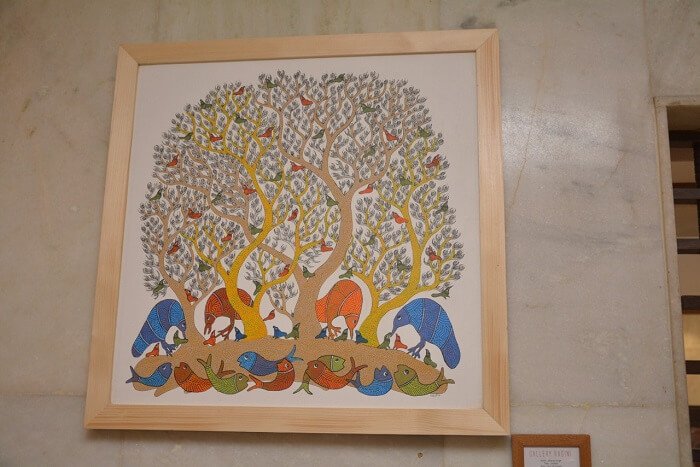

I visited the Patangarh during the winter, avoiding the harsh summer heat, while writing a research paper on vernacular housing in the region. At first glance, it is like any other village in India, some ‘pucca’ houses stemming off the highway and towards the fields. But on dwelling further through the gentle slopes, you’re met with their beautiful small mud houses, decorated with the traditional style of Gond painting. Every mural has a significant meaning or narrative which stems from the local stories, the folklore.

The words of folklore are rarely written down and only now, when the fear of oblivion looms. During my time in Patangarh, the people welcomed me into their homes and told me not just about the architecture I was studying but about their mural, paintings, rituals and most importantly, their stories. Every villager had a story to tell, most of all the matriarch of Dhavat’s family.

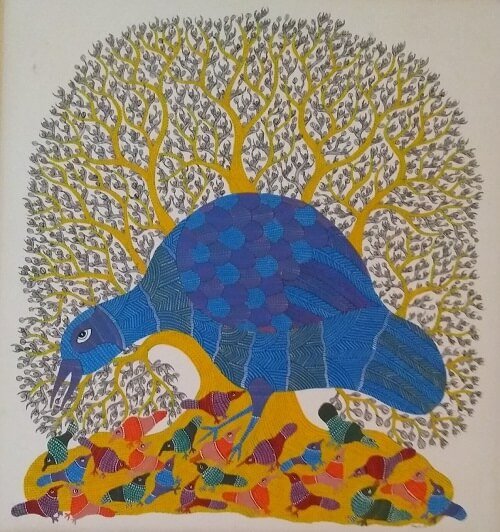

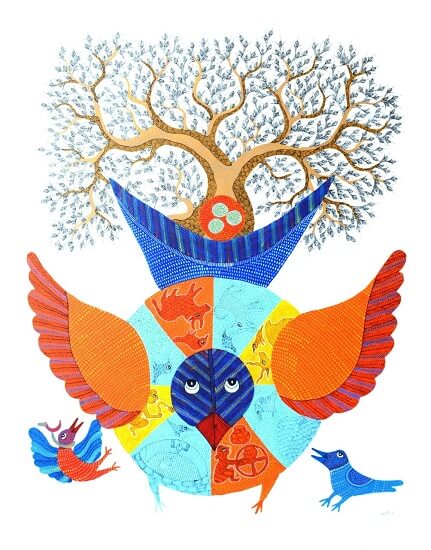

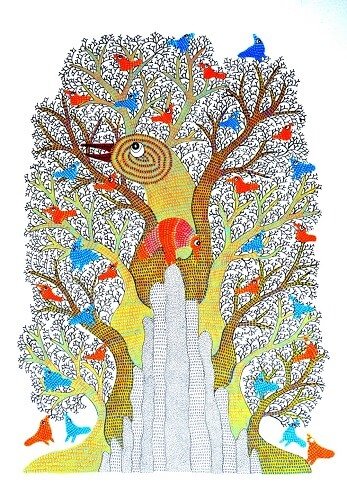

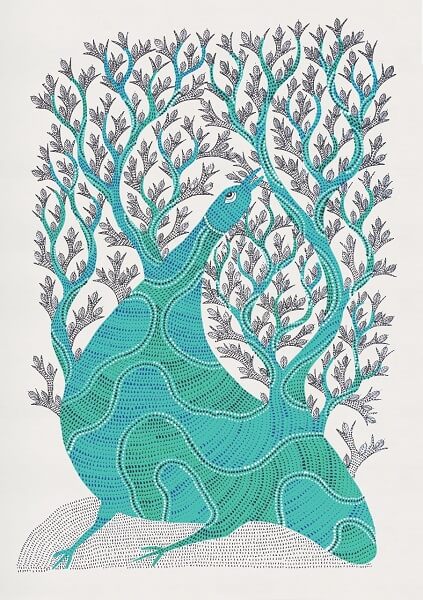

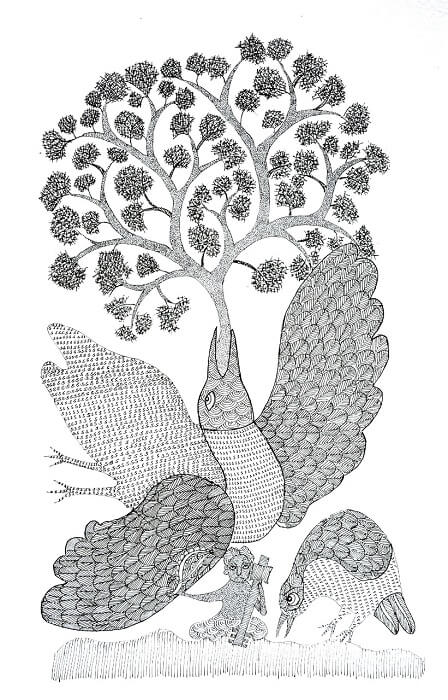

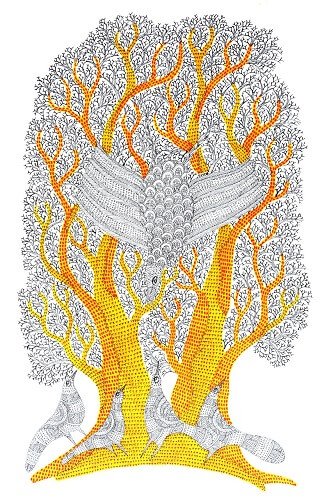

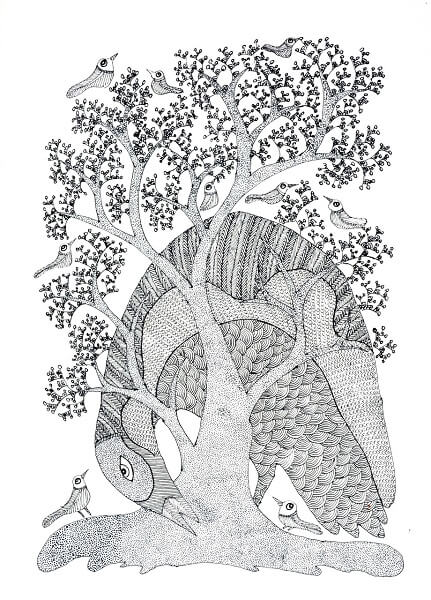

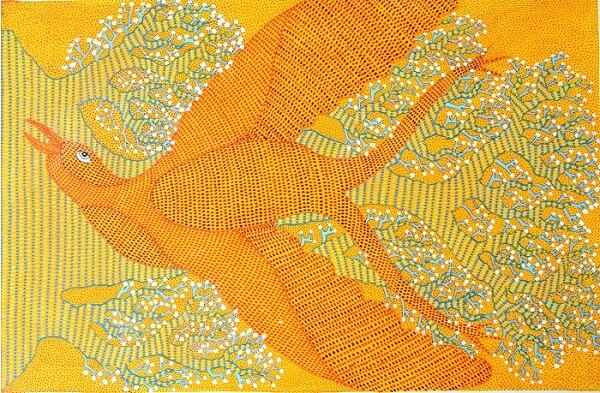

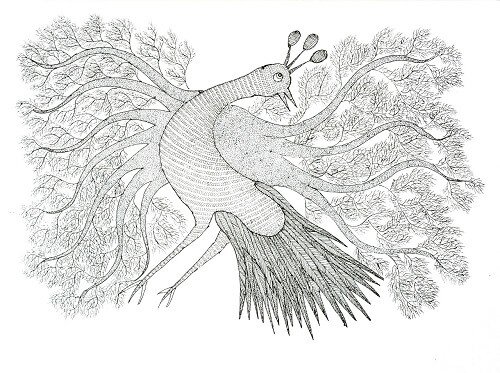

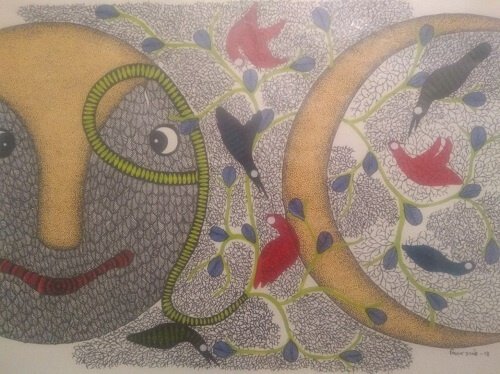

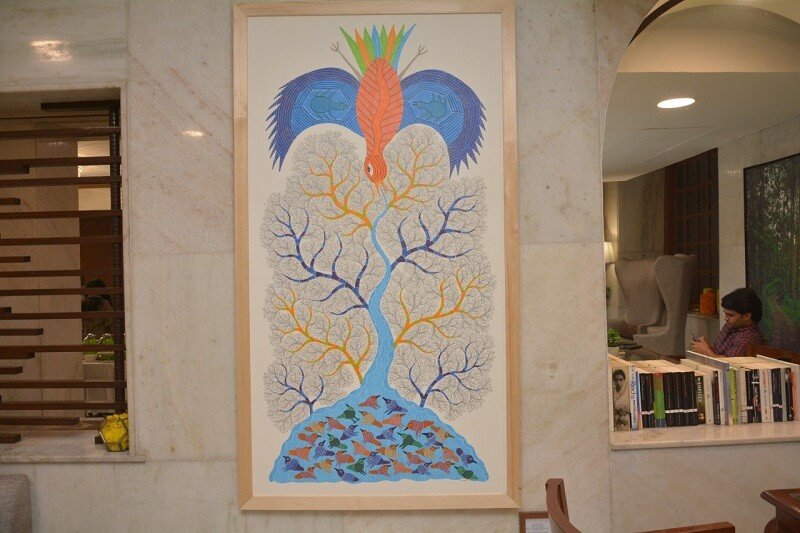

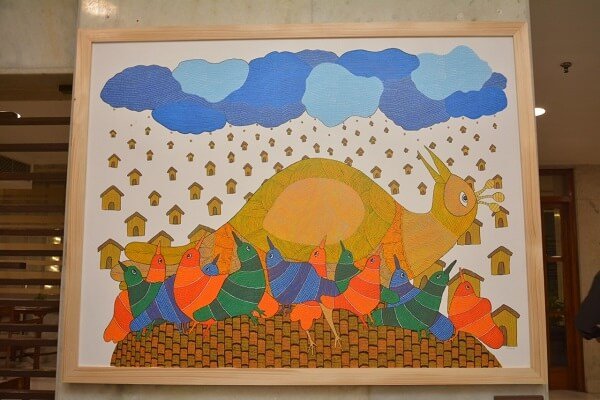

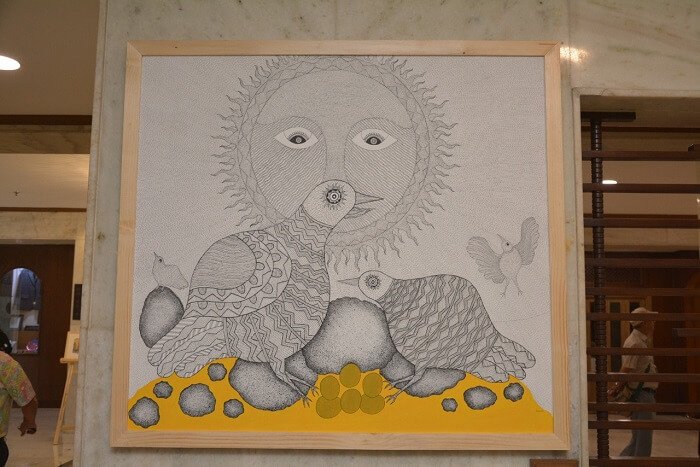

The paintings that Dhavat creates reflect the same beauty and charm as the village he hails from. He dwells into the different stories – of birds ready to hold up the sky, peacocks losing their crowns to vanity and even the coming into being of the Earth – with attention to detail, crafting a narrative that draws and retains ones attention.

When he talks about his work, Dhavat turns into a storyteller. He takes pride in the small eccentricities of the stories, brightens as he retells a childhood favorite and laughs at the peculiar behavior of some characters. He seamlessly makes his way through different stories, pausing to highlight details on paintings that represent elements of a plot or character.

Through his work, Dhavat honors his roots and it helps him draw his culture into the contemporary world rather than watching it retreat into museums.

Ragini Jyoti Jain

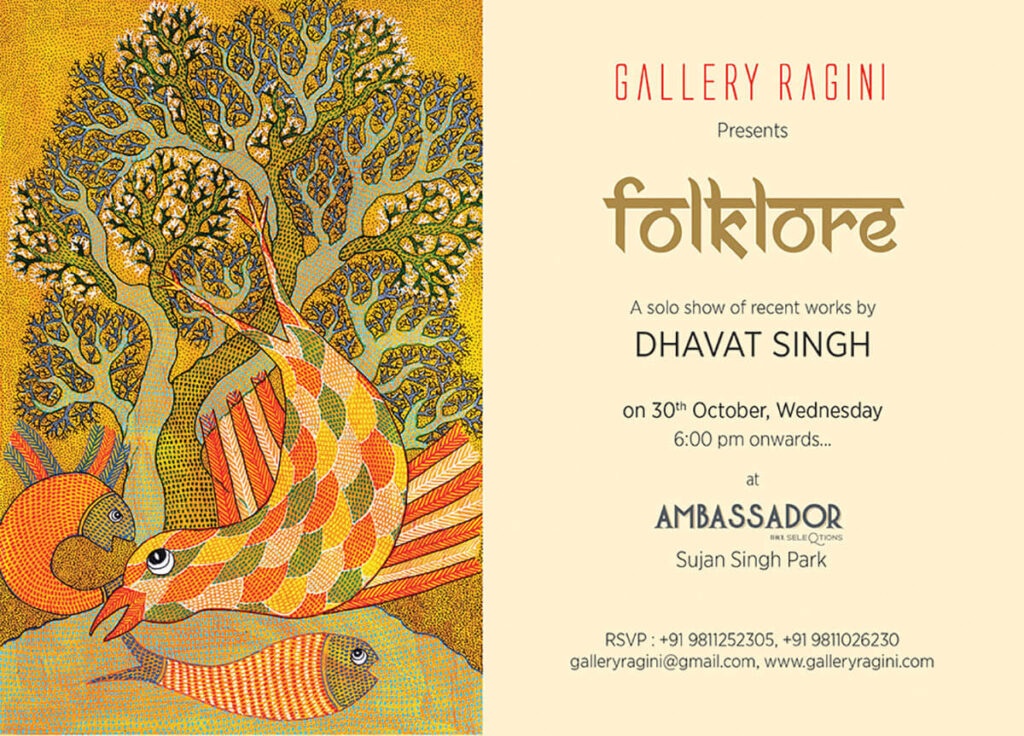

VENUE: Ambassador, New Delhi- IHCL Seleqions,

Sujan Singh Park,

Subramania Bharti Marg,

Khan Market, New Delhi-110003

DATE: 30th October 2019